The Plants of the Olentangy River Trail

(The Olentangy River Trail woodlands near the Neil Avenue apartments)

It would appear that three weeks into the school semester, I am officially inundated with everything PLANTS! From mosses to shrubs to trees to vines to ferns, there is so much to learn and see. I can’t imagine going outside and trying to find all that in the wild. Except… that is exactly what I am going to try and do! Before I get to ahead of myself, I am going to begin by finding a few new tree species, woody vines, flowering plants, and last but not least, poison ivy.

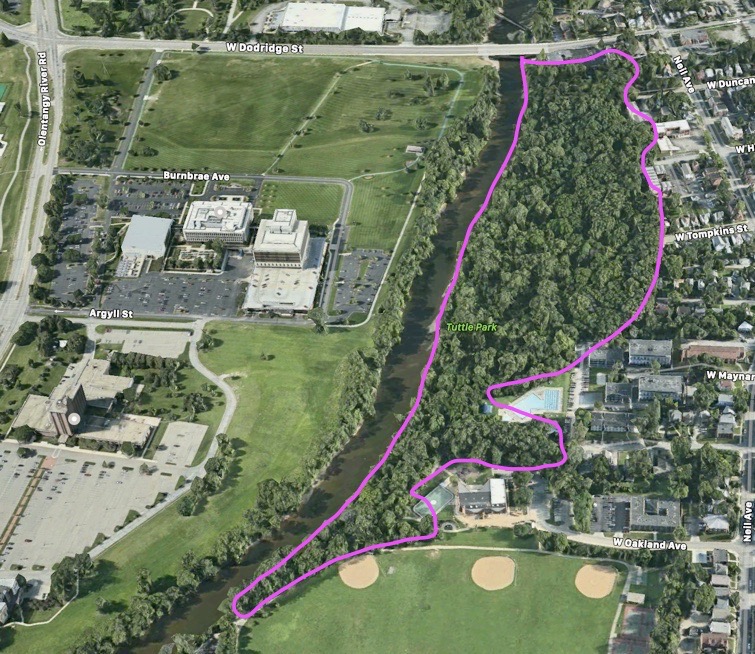

My botanical survey takes place along the Olentangy River Bike Trail close to the Neil Avenue Apartments. As you can see in the map below, my plant survey begins on the south end of Tuttle Park on the edge of some recreational fields. The bike trail and surrounding woodlands continues north (west of the apartments) all the way to the Dodridge Road bridge where I end my plant walks. This woodland is located to the east of the Olentangy River and is located in its floodplain. Therefore, many of the tree and plant species reflect this type of habitat with some floodplain specialists being present in the woods including Silver Maple and some Swamp White Oak. While on site, I saw a variety of cool bird species including the Wood Duck, Osprey, and some fall migrating warbler species.

Here is a visual of the map to help give a clearer idea of the location as well:

My botanical survey takes place in the area encircled by the pink line. It begins close to Tuttle Park and extends along the Olentangy Trail all the way up to the Dodridge Road bridge.

Now that I have figured out where my botanical surveys will take place, the adventure truly begins! To start with, I identified two new tree species that I haven’t blogged about before: the black locust and the catalpa.

Black Locust

(Robinia pseudo-acacia)

Our first tree is the black locust. It is a normally medium-sized tree with pinnately compound leaves. It can be distinguished from the honey locust by looking at the shape of the compound leaflets. The leaflets on the honey locust are pointed more pointed and skinny and also do not overlap over other leaflets. On the other hand, the leaflets on the black locust clearly overlap and also are more of an oblong shape rather than pointy. From farther away, the honey locust also has a ‘finer’ leaved appearance in comparison to the black locust.

A more zoomed out view of the black locust branches with their pinnately compound leaves.

Some cool facts about the black locust are that its seeds are a food sources for a variety of wildlife including bobwhite, pheasant, Mourning Dove, cottontail rabbit, snowshoe hare, and also White-tailed Deer (Petrides, 127). The seed pod is fully ripe when it turns a dark brownish black color. The indehiscent fruit is considered a legume because as a member of the Fabaceae family. The fruit is unicarpellate and splits down two sutures after the fruit reaches maturity. Despite how helpful this tree is for wildlife, it can be poisonous to livestock. This tree’s wood is also known for its durability and strength which makes it a great wood for creating long-lasting fence posts.

In this black locust leaf, you can see how the leaflets are oblong and not at all pointy unlike the honey locust. The leaflets also slightly overlap one another unlike the honey locust.

Catalpa

(Catalpa spp.)

Our next tree is quite an interesting specimen, the catalpa! Some features of this plant are its leaves in pairs or in whorled 3’s. The leaves are entire and simply and are a chordate shape. The leaves are quite large and can be up to a foot long! The silhouette of this tree is quite distinctive in that its ‘blocky’ shape is quite disruptive on the landscape in comparison to many of our ‘finer’ leaved trees. See in the photo below to observe just how much the branches stand out compared to the other trees around it. It is important to not be confused with the eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) that has much daintier branching compared to the short and stout branches of the catalpa.

A catalpa tree full canopy

The catalpa tree has a history of being quite useful to people. It has a strong and sturdy bark that has been historically used for fence posts and the tree was even planted for this purpose. Another fun fact for this tree is that the catalpa caterpillar of the catalpa sphinx moth often eat large amounts of the leaves on this tree. These “catawba worms” which are the moth larvae are known to be prized fish bait (Petrides, 85).

Catalpas also have seed pods that are quite unique in structure and hang down at sometimes over a foot or even two feet long depending on the species. Despite looking like it has ‘beans’ it is not in the Fabaceae (bean) family, and is instead in Bignoniaceae.

Now that we’ve taken a look at a few new trees. It is time for us to discover to new fall flowering plants. These two species are Wingstem and Tall Boneset

Wingstem

(Actinomeris alternifolia)

This flowering plant was in plain sight right on the edge of the Olentangy Trail in view of bikers and walkers alike. Its bright yellow flowers immediately grabbed my attention. I set to work using my Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide by Lawrence Newcomb to identify this fall beauty. I decided on Wingstem because this wildflower has alternate arranged leaves that are slightly toothed along with flowers that contain more than 7 parts. The petals are also quite droopy instead of being supported which is a feature that is also helpful in identifying the Wingstem.

One awesome fun fact, according to prairie moon.com, calls the Wingstem a “golden honey plant.” This nickname for the plant comes from the fact that it supports a relatively high number of pollinators with particular high diversity in the bees and wasps. It is also a host plant for the Silvery Checkerspot butterfly, Summer Azure butterfly, and Gold moth.

Wingstem right along the Olentangy trail (showing a view from farther back).

Tall Boneset

(Eupatorium altissimum)

This flower made its appearance to me right along the bankside of the Olentangy River. I looked up this plant in the Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide as well using the knowledge that it had indistinguishable parts, white flowers, and leaves that had some serration or teeth. The shape of the leaves themselves were also fairly distinctive. This is what led me to the conclusion that this plant is a Tall Boneset. This plant normally prefers open woods and prairies which is interesting because of where it was found (on a riverbank near the edge of a human created trail).

Tall Boneset is a fall wildflower and in the image you can see the white flowers in bloom.

Tall Boneset is interesting from an ecological perspective in that it can easily take over the woody edges during the summer months. It is not an invasive plant because it is a native perennial and has a natural ecological niche, but some sources do consider this plant to be weedy (coldclimategardening.com). It is a rhizomatous plant, meaning that it has rhizomes under the surface of the soil which allow it to quickly produce colonies of the plant in high numbers. It would seem that the Tall Boneset is quite a prolific plant!

The leaf shape, serration, and plant height are all good clues for identification.

Now that we have seen a couple of flowering plants, we will now look at two vining plants in our forest community. The two species I will give tips on identification for and photos are the Virginia creeper, and the riverbank grape.

Virginia Creeper

(Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Virginia creeper is an extremely distinctive plant in that it has leaflets that are serrate and five leaflets per leaf that are arranged in a palmately compound fashion. The leaves are a dark green in the summer, but they then turn a gorgeous yellow in the fall before they drop for the winter. When there are no leaves on the creeper and it is vining up a tree you can tell the vine is from the creeper if it does not wrap tightly around the tree and lacks hairs on the vine. This is in comparison to other vines like poison ivy.

As a vining plant, Virginia creeper’s palmately compound leaves can be found up high vining around a woody plant.

Even though Virginia creeper can be found on trees it can also be found in carpets on the ground as well like in this photo.

Riverbank Grape

(Vitis riparia)

Riverbank grape is yet another vining plant that I found! It often coats the tops of small trees where it vines and can prove to be quite thick! One diagnostic characteristic is the leaf shape in that it contains serration and begins as a chordate shape before it ends in three distinguishable points. They are produce clumps of fruit that are popular with the local songbirds as well. The berries are green before they are ripe before richening into a deep purple.

A close-up of the leaves of the riverbank grape.

A zoomed out view of riverbank grape vining on another plant.

Poison Ivy

(Toxicodendron radicans)

And of course, last but not least, we have to take a look at poison ivy… if only to avoid it! It is important to know the field marks of this potentially poisonous plant so that we don’t accidentally make contact with it. I personally am not highly allergic to the plant, but it is still very interesting to see the various forms this plant can take.

Poison ivy berries! Yum! I’m sure the birds will enjoy them when they are ripe.

Poison ivy can carpet on the ground and look like a small ground dwelling plant and it can also vine up larger structures, like trees, to form trifoliate leaves higher up on the vine. In the picture above, you can see that the ivy has white berries this time of the year. In the photo below, you can see a more zoomed out version of the plant’s branch. This particular individual had vined up a tree and put out a branch over 15 feet high. The berries are apparent and also the trifoliate leaf pattern (also known as a three part pinnately compound leaf). The vines, even though I don’t have a photo of them, tightly wrap around the tree and also have hairy roots. This is an important identification tool for the winter!

Vine form of the poison ivy branch

As well as in the air, it is important to avoid leaves of three on the ground as well. In the photo below, you can see the ground form of the poison ivy is just bending its form over the grass at the edge of the Olentangy Trail. Even in the most manicured of places, poison ivy can still show up!

Ground form of poison ivy forming small plants with a trifoliate leaf arrangement.

Well! That concludes my first botanical survey at the Olentangy Bike Trail near the Neil Avenue apartments. Not only did I discover new plants, but I had a lot of fun and I am excited to see what my next plant adventure brings!]

Updated October 11, 2021

Plants of the Olentangy River Trail Part 2!

Welcome to Part II of my Botanical Survey at the Olentangy River Bike Trail. For the map of the area that I surveyed, see the first update on my post. In order to get a good idea of the quality of the site I am using the Coefficients of Conservatism (CC) that were assigned by experts on Ohio Plants to help calculate the Floristic Quality Assessment Index for the habitat. This index can help estimate the overall quality of the site. It does not include invasive plants which I have placed in a separate category.

Here are both of the terms defined:

Coefficients of Conservatism (CC): The CC is a number from 0-10 that is assigned to individual plant species by Ohio Plant experts that have knowledge of the native flora of the state. The higher the CC the more likely the plant species is indicative of high quality habitat and the species with a lower CC are more akin to areas of disturbance and can survive in a wide variety of conditions.

Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI): The FQAI is a method of bio assessment where one can take the inventory of the plants in their specific site and plug the CC values into a formula in order to come up with an estimate of the nativity of the species and habitat quality.

In order to calculate the FQAI of the Olentangy River site, I did an inventory of many wildflower, vines, shrubs, and trees in the area. It is not a comprehensive list, but it should give us an idea of how good the habitat is based on the plant species I found there.

List of Native Plants:

Common Name (Scientific Name) (CC Value)

- Ohio Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) (6)

- American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) (7)

- White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) (3)

- Riverbank Grape (Vitis riparia) (3)

- American Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) (4)

- Box Elder (Acer negundo) (3)

- Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) (5)

- Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) (3)

- American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) (5)

- Silver Maple (Acer saccharum) (3)

- Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) (6)

- Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) (3)

- Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) (6)

- Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) (3)

- Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) (6)

- Honey Locust (Gleditsia triacanthos) (4)

- Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacadia) (0)

- Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipfera) (6)

- Roundleaf Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) (4)

- Wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia) (5)

- Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) (1)

- Wood-nettle (Laportea canadensis) (5)

- Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) (3)

- Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) (2)

- American Basswood (Tilia americana) (6)

- Spice-bush (Lindera benzoin) (5)

List of Invasive Plants:

- Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii)

- Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

- Winter Creeper (Euonymus fortunei)

- Moth Mullein (Verbascum blattaria)

- Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

- Catalpa (Catalpa spp.)

- White Mulberry (Morus alba)

- Burdock (Arctium spp.)

Substrate-picky Trees:

- Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) (3)

- American Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) (4)

- American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) (5)

- Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) (6)

The calculated FQAI of the Olentangy River Trail is 20.98. I calculated this number by adding up the CC’s of all of the plants I found for my inventory then I divided this by the square root of the sample size (number of plants in the inventory). 1-19 indicates low vegetative quality while 20-35 indicates a higher vegetative quality. Finally, 35 and above indicates a “Natural Area” level of quality. According to this FQAI measurement, the Olentangy River trail is on the lower end of high quality vegetation. I would be curious if there is a measure to factor in invasive plants because there were many of these! Some that I got only to genus I didn’t even list.

Note that for the following plants unless otherwise stated the source material is Petrides’ Peterson Guide to Trees and Shrubs.

Four High CC Plants

American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) (7)

The American Sycamore is a lowland tree with distinctive mottled brown bark with lighter white patches. Little flakes of the bark occasionally fall off in long-papery slats. The leaves are also quite distinctive as well and are very large. It is often seen on the edges of rivers. It is known as the most massive tree in the Eastern United States, and indeed, it towers over all the others along the Olentangy River.

The sycamore has a high CC because it a specialist plant of the bottomland forests. This means that the Olentangy river must be great habitat for it since it is in a riparian zone along the river. This tree was the highest CC plant I found of 7!

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) (6)

The Pawpaw is really gorgeous understory plant that has large alternate leaves that are arranged in a pinnately compound fashion. The pawpaw is known for its fruit that tastes somewhat between a banana and a mango (I can personally attest to how delicious the fruit is!). Other wildlife also loves the fruits as well! It is also recognizable by its bud all year that looks like a dark-colored crab claw.

According to blossomnursery.com, the pawpaw prefers moist, bottomland habitat and won’t grow in any others which may be why it has a higher CC. As a picky plant, it needs a higher quality habitat to persist.

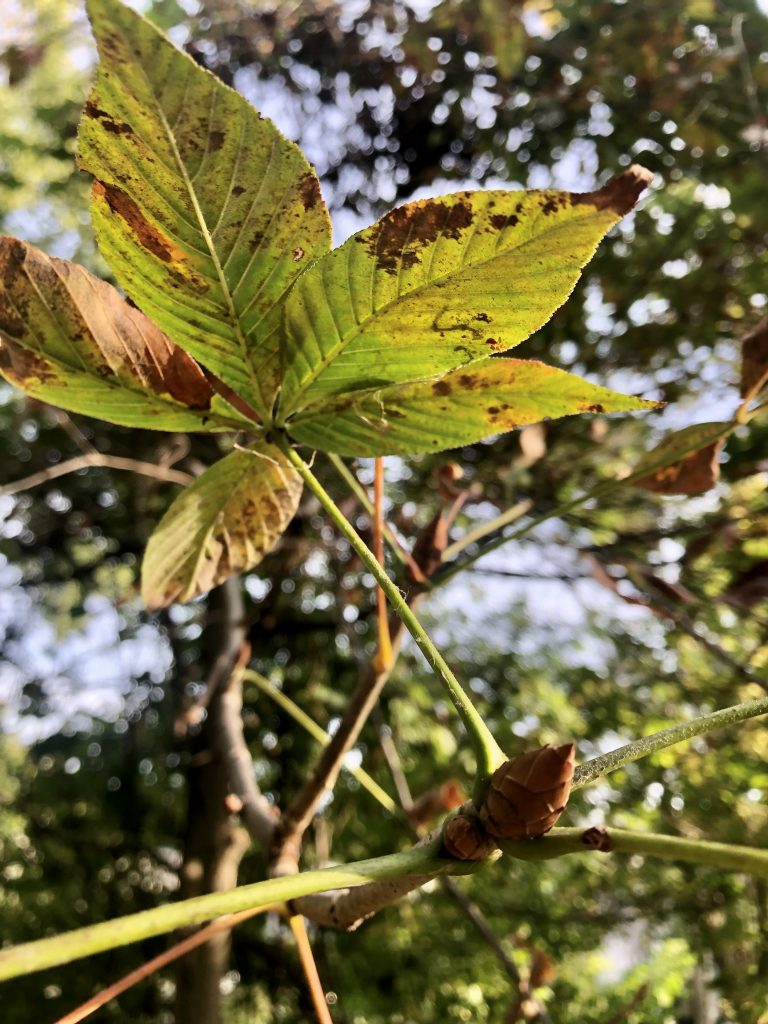

Ohio Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) (6)

The Ohio Buckeye can be identified by its five leaflets arranged in a palmately-compound fashion. The leaves are also arranged oppositely! When the tree does not have leaves it is still distinctive since it has large, dark, imbricate terminal buds (see in the photo!). The bark also reminds me of a very sickly looking tree which can be diagnostic. The twigs also emit a fowl odor when broken.

One interesting fact about the Ohio Buckeye is that its nuts are poisonous, so I wouldn’t recommend taking a bite if you’re hungry (I always am…). The nuts can be great keepsakes for Ohio State students since their mascot is the Ohio Buckeye nut, but they are NOT A SNACK!

The Ohio Buckeye prefers a habitat with a certain set of standards. It prefers to grow next to streams and rivers but not TOO close to these water forms. It prefers moist soils that are not too wet or too dry. It usually does not do well in human modified landscapes since it prefers to be an understory tree in partial-shade.

Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipfera) (6)

Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipfera) (6)

The Tulip tree, also known as the Tulip or Yellow Poplar, has very distinctive leafs that have a blunt ended center lobe. They kind of remind me of a cat’s face (though that may be a bit of a stretch!). The twigs are also hairless with completely circling stipule scars. You can also crush the buds and leaves and find that they are spicily aromatic! One cool fact about the Yellow Poplar is that the seeds are readily enjoyed by squirrels and other songbirds.

This tree is one of the largest in bottomland forests second to the American Sycamore that we already saw! Like the sycamore, it also prefers the bottomland habitat and usually only persists in areas in the riparian zone. This is most likely why it is a CC of 6 in that it usually only persists in a healthy version of this ecosystem.

Four Low CC Plants

Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) (0)

The Black locust has pinnately compound leaflets that are oblong and at times nearly round in shape. It usually has long black bean pods that are quite distinctive during certain times of the year. This tree’s wood can be used in a variety of circumstances such as a wooden flooring, furniture, fenceposts, and railroad ties.

The black locust has the lowest CC possible for a ‘native’ plant. It is considered to be quite invasive in an ecological sense since it often displaces and crowds out other natives. It is not necessarily a non-native but it has been expanding its historical range. I’ve talked to several botanists about this tree and there is general disagreement whether it is native or truly an exotic invasive. It is a tree that takes advantage of disturbance meaning that it is the opposite of a high-quality and stable habitat plant with a high CC.

Robinia pseudoacacia (Black Locust with a CC of 0)

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) (2)

The Virginia Creeper is another example of a plant with a low CC. It does well in nearly every forest habitat that it is introduced to which is why it may have a very low CC. It can take advantage of disturbed habitats so it is not necessarily indicative of quality and stable forest ecosystems. Remember that low CC plants aren’t always bad for the ecosystem but just don’t indicate high quality. This has a low CC of 2 probably because it takes advantage of disturbed sites as well.

One can identify Virginia Creepers by the fact that they are a vine that is either on the ground or crawling of the trunk of the tree. They vines usually have distinctive roots (but not hairy like poison ivy) and have serrated leaves that are composed of five leaflets arranged palmately. The berries on the Virginia Creeper are present throughout the winter and are often a food source for Yellow-rumped Warblers, chickadees, nuthatches, and other passerines.

Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia Creeper)

Box Elder (Acer negundo) (3)

This medium-sized tree is actually a maple which is why it is sometimes known as the Ashleaf Maple. It is recognizable by its green stems and also by the fact that it has that its leaflets are tripinnate (resembling a split maple leaf). These features are the best way to recognize the Box Elder. Its leaves are also oppositely arranged. A couple cool facts about the tree is that its sap can be used to make syrup like other maples and squirrels and songbirds like to feed on the samaras.

This tree has a low CC because it will grow anywhere with somewhat moist soils and it is not as nearly as picky as the Ohio Buckeye when it comes to finding soils that are not too moist or too dry. It sometimes is found in the same habitat as the Ohio Buckeye though. It also is another understory tree that often breaks out during times of disturbance.

Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) (3)

The Black cherry is most distinguishable by its patterned bark. The dark color of the bark stood out to me and its rich color is only rivaled by the Black Walnuts that were also present along the Olentangy Trail. The bark’s pattern is also recognizable in that it is a little bit peely but still somewhat tight. The smaller branches also have reddish bark as well.

The fruits are quite attractive to a variety of wildlife. These drupes are consumed by Ruffed Grouse and Sharp-tailed Grouse. In areas within their range, they are also enjoyed by the American Black Bear (Ursus americana). From a human perspective, the berries are quite bitter but can be used to form a nice jelly.

This tree also has a lower CC of 3. This is probably because it can utilize a whole variety of habitats. It can thrive in dry or moist woods in a variety of climates and ecosystems. It also takes advantage of areas of disturbance due to humans such as roadsides and fencerows.

Four Invasive Plants

Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii)

Ahhhhh honeysuckle… anyone who knows me is well aware of the struggle I feel with invasive wildlife and plant species. It’s not the animal’s or plant’s fault they were stuck here by us! But goodness, with the invasive of honeysuckle in our forests it is hard not to feel angry. Or to pull out your clippers and poppers and get to work…! This was by far the most common plant I saw along the Olentangy. It was EVERYWHERE. It has bright red berries in pairs (two on each side of the branch) and the bark is distinctively orangish and stringy (eww). This plant also has oppositely arranged leaves since it is in the Caprifoliaceae family (madCAPbuck if you remember for oppositely arranged plants).

One interesting fact about the honeysuckle is that it has been changing the feather colors of some birds in our forests due to how common it is. The red dyes in the berries are ingested by the birds and then incorporated in their feather colors when the pigments are used. Certain feathers on birds use carotenoid pigments whose metabolic precursors are the birds’ diet. Since there are SO many honeysuckle there has been a noticeable impact on the color. A classic example is the reddening of the wing tips on the Cedar Waxwing.

Lonicera maackii (Boooooooooo hissssss)

Winter Creeper (Euonymus fortunei)

NOT ANOTHER INVASIVE PLANT!!! (oh there are always more) The Winter Creeper often goes unnoticed in our forests but it is quite prevalent. As a young plant it often is ground cover (see the right photo below), but when it matures it can grow up the sides of tree to fruit and sometimes entirely cover the bark (see left photo). It’s not a plant that is talked about as much but that doesn’t mean it isn’t quite a pest! One (fun?) fact about this plant is that is an evergreen meaning it maintains its green lives all year round. This plant’s natural range is Japan, China, and Korea.

*Special source for invasive info: www.invasive.org*

Moth Mullein (Verbascum blattaria)

What a strange plant with an even stranger name! It is in an even stranger plant family called the Scrophulariaceae. It is an herbaceous plant that has flowers that have white petals with a purple center. The central stem is stout, ribbed, and also glabrous underneath the inflorescence. My source material is from Illinoiswildflowers.info. A great website for learning about invasive species!

This species’ pollen is collected by a variety of flies, bumblebees, and Halictid bees, but it probably isn’t very effective at cross-pollination. Little is known about how this plant interacts with the native species of our forests since it is nonnative and typically cultivated.

Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

Boooooo and hissssss to the Tree-of-Heaven. Out of all the invasive we have in our northeastern United States forests this one may be the worst. Many argue that it is! I spoke with a retired Pennsylvania forester who is a friend of my family and he described entire stretches of Tree-of-Heaven invading disturbed areas of forests. This invader is a worst nightmare scenario and is extremely difficult to control since it is so prolific. This tree was introduced from China.

This tree can be recognized by its smooth gray bark and sharply lanceolate leaflets that are arranged in a pinnately compound fashion. This tree is bad news. Eeeeeeee. (sorry this post has made me too angry gotta take a break ✋😤). I have so many Tree-of-Heaven in my neighborhood.

- Tree-of-heaven photos showing the fruits and leaves.

Four Substrate-Associated Plants

For the next (and final!) session we have a few plants that are substrate savvy. Again, my reasoning for choosing these plants comes from the Jane Forsyth article that is cited on other pages. I couldn’t find four only for lime loving areas, but I did my best to find a few specialists!

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

The Eastern Redbud, according the article, prefers areas where limestone is present at “very shallow depths below the ground surface.” It particularly likes sites that are higher and drier in the soils typically. I would say that this redbud is in the right place then! It is located in the limestone substrate region of Ohio and it is a decent distance from the river so it would be drier than closer to the riverbank.

This plant is known for various parts of it being edible and also some parts that are not edible! Be sure when sampling this tree to enjoy the leaves but do NOT eat the bean pods. These pods, which are more formally called legumes, are quite poisonous to humans. The redbud can be recognized by its chordate leaves and thin twigs.

American Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Another one of our substrate-specific plants that Jane Forsyth mentioned is the American hackberry. It is one of my favorite plants since it has fuzzy leaves that have a very distinctive yellow-green color. The leaves often get disease so sometimes they look sickly (like in this photo). The bark is also unique since it is warty and a grayish-brown color. The leaves are also serrate and alternately arranged like all plants in the Ulmaceae family.

The hackberry according to Jane’s article also likes high, dry sites on limestone bedrock and is also common in the floodplains in most of unglaciated Ohio. It would make perfect sense that I saw a ton of this plant since my botanical survey took place in the Olentangy River floodplain.

American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

The American Hornbeam in another tree that we also saw on our trip to Cedar Bog and Deep Woods that is also known as Musclewood. It has a very distinctive bark that looks like a flexed muscle, it is also a lighter color like a beach. The leaves are also entire and double-serrated.

This tree according to my research, prefers moist and acidic soils. It grows best in partial shade as well and likes to grow alongs streams and rivers. I have found this plant in many parts of western Ohio despite the fact it prefers acidic soils, I don’t think it is entirely restricted to these areas despite its preferences. It is in a good place to grow though since it was right along the Olentangy River and this tree appreciates moist soil conditions.

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

The Bur Oak loves lower elevations along with moist woodlands and bottomland forests. According to the article, it is a Praire-margin tree meaning it appreciates being on the edge of a forest overlooking a prairie! I have often seen these trees towering over prairies as loners. Such was not the case at the site. The tree I found was small and right by the river. I think it may have been planted there as part of a restoration project.

This tree can be recognized by its many and smooth lobes (like a white oak but more lobes). It also has diagnostic furry caped acorns!